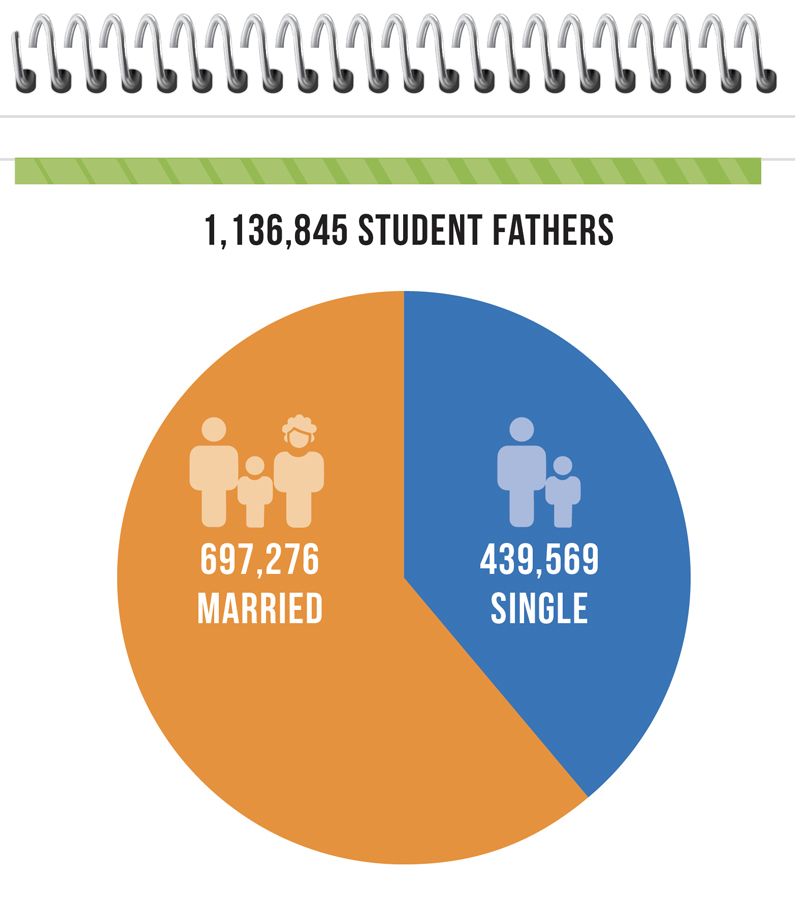

Among the one in five postsecondary students who are parents, there are close to 1.1 million student fathers. A growing body of research on student parents in recent years has shed more light on this sizable student population, but very little research has focused specifically on student fathers. This dearth of information constrains institutions, policymakers, and advocates from understanding who student fathers are, why they enroll, and what can support their success.

Ascend at the Aspen Institute takes a two-generation approach to its work and applies a gender and racial equity lens to its analysis. Two-generation approaches provide opportunities for and meet the needs of children and the adults in their lives together. We believe that education, economic supports, social capital, and health and well-being are the core elements that create a legacy of opportunity that passes from one generation to the next.

This chartbook synthesizes the available research on student fathers[i] to help inform the field’s efforts to support the success of all student parents. Given the gaps in the research on student fathers, we also reviewed research on male college enrollment and male adult learners’ experiences. The chartbook concludes with a call for research on student fathers in specific areas.

Key Findings on Student Fathers in Postsecondary Education

- Student fathers are most likely to be white, while student mothers are most likely to be women of color.[1]

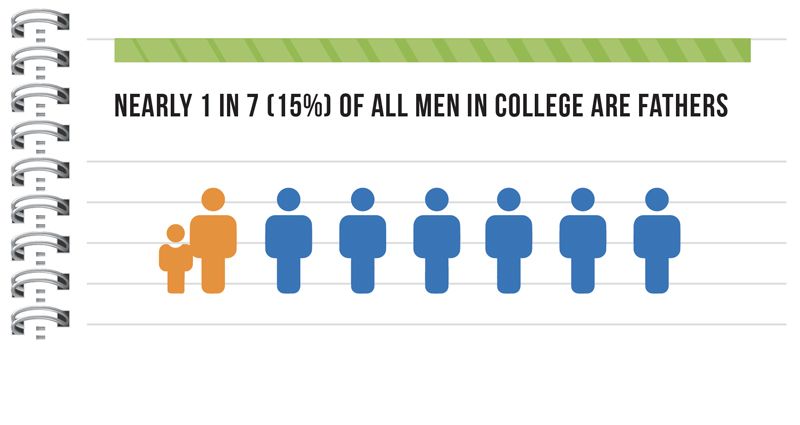

- Available data show that some groups of men in college are disproportionately more likely to be parenting: nearly 1 in 7 (15 percent) men in college are fathers, with Black, Native American, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander men more likely to be parenting.

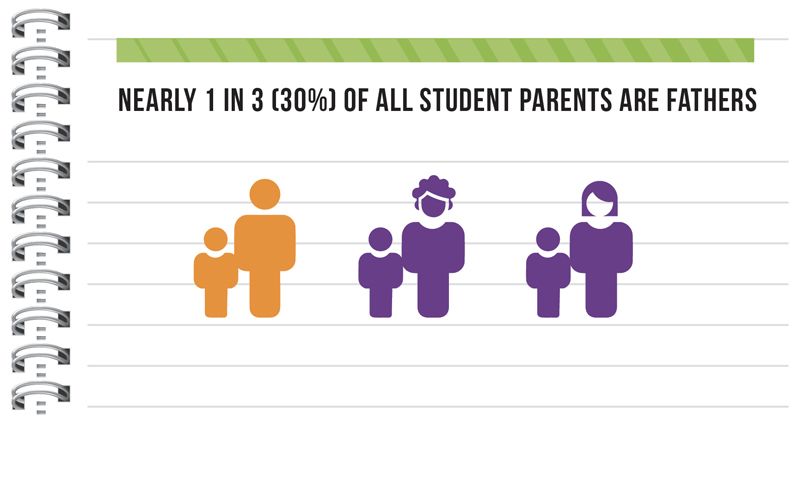

- Although most student parents are mothers, nearly one in three (30 percent) are fathers.

- Student fathers are more likely than student mothers to have child care help and feel excited and stimulated by college. But student fathers are also more likely to consider suicide and to stop-out of college.[2]

- Black men are a distinct group among student fathers. While student fathers overall are more likely to be married and student mothers are more likely to be single, Black student fathers are more likely to be single than married. Black student fathers also have the highest rates of stopping out of college across race and gender and experience especially high levels of basic needs insecurity.

- More research and data disaggregated across social identities are needed, especially related to race, marital/single status, and age.

“Fathers want an education, they also want a conducive and feasible route to accomplish such a tremendous goal, but they need a tangible map on how that’s going to happen.”

– Ariel Ventura-Lazo,

2020-2021 Ascend PSP Parent Advisor

Who Are Student Fathers?

Around 4 million college students are parents, representing more than 1 in 5 college students. Over the last decade, a growing body of research has explored the demographics, experiences, and outcomes of student parents, but little research has focused on student fathers specifically.[3][4][5][6]

Analysis of data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study shows that 15 percent of all men enrolled in college are fathers, with higher rates of fatherhood among Black, Native American, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander students (21 percent, 21 percent, and 23 percent, respectively) (Chart 1).

Student parents are most likely to be students of color, with women of color disproportionately more likely to be raising children as single parents while in college. Student fathers, however, are more likely to be white men and married. Black student fathers are the only group of student fathers that are more likely to be single than married (Chart 2).

Marital status is an important, though not definitive, indicator of the levels of personal and financial support available to a student father and his child(ren). For instance, other research shows that nearly nine in ten[7] single mother students in college live in or near poverty and spend nine hours per day on caregiving,[8] underscoring the time and financial constraints facing single parents pursuing a degree.

Further exploration of student father demographics across races, including Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander and American Indian/Alaskan Native, is essential if we are to better understand our student father population.

Student parents are more likely to be older than non-parenting students, with an average age of 32. Nearly two in three (65 percent) student fathers are 30 or older, with Black and white student fathers the most likely to be older students. Notably, Black student fathers are least likely to be within the “traditional” college age (i.e., ages 18-24), while Asian student fathers are the most likely (Chart 3). These trends mirror broader college enrollment demographics. In 2018, Asian students aged 18-24 accounted for 56 percent of college students, and Black students in the same age group made up 31 percent.[9]

“I myself have predominantly raised my daughter on my own, and while pursuing my GED, I was working a full-time job as a shift supervisor at Starbucks, along with paying for my daughter to go to daycare. After rent and all of my expenses, including daycare, I would very often stay with less than $100 for the week.”

– Christian Ortiz,

2023 Ascend PSP Parent Advisor

What Are Student Fathers' Experiences?

When researchers, policymakers, and postsecondary administrators understand a student population’s experiences, they can more effectively identify ways to support that population. Although there are some scholarly articles or reports that have had student fathers as participants, most student parents in the studies identify as women.[10][11][12][13] For example, a recent study on the experiences of student parents of color in community college included 67 participants, and only three self-identified as men.[14] More research on the specific experiences of student fathers would help the field understand the supports they need to succeed.

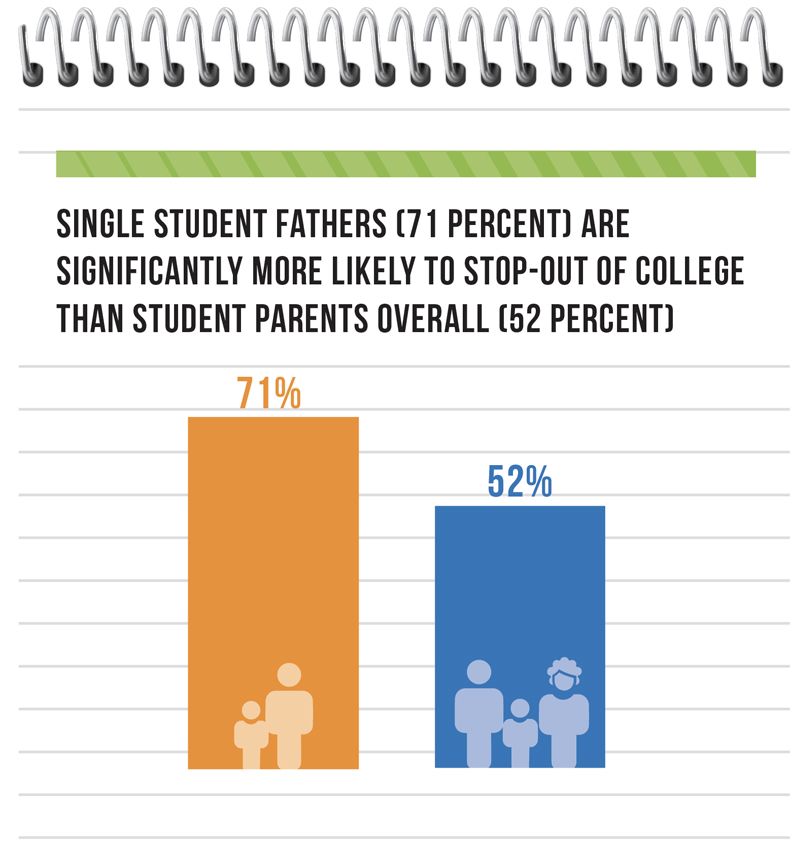

Enrollment and Persistence

According to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR), single student fathers (71 percent) are significantly more likely to stop-out of college than student parents overall (52 percent).[15] Black and Latinx student fathers (72 percent and 57 percent, respectively) are more likely to stop-out than white student fathers (57 percent). From the demographic data, we know that Black student fathers are more likely to be single than married, but more research on stop-out trends across race, gender, and marital status is needed to better understand barriers and supports that affect completion.

IWPR points to “time poverty” — the lack of adequate time for day-to-day responsibilities — work factors, lack of child care, the increasing financial burden of higher education, and uncontrollable life circumstances among the reasons student parents stop-out and re-enroll. Student parents, often motivated by a desire to provide for their children, re-enrolled based on personal and career goals.

Most of the existing scholarship focused solely on student fathers[16][17][18][19][20] has narrowly tailored research methods, research questions, and participant demographics, making it difficult to draw reliable conclusions about the reasons for high stop-out rates among student fathers specifically.[ii] However, findings from a recent qualitative study on Hispanic and African American student fathers offer tailored insights.[21] Several important themes from the scholarship are consistent with IWPR’s research, including that student fathers:

- Are motivated to enroll and persist because of the desire to support their children. Student fathers wanted to provide for their children, and they felt earning a degree would allow them greater earning power.

- Feel time pressure because they have to balance work, education, and family commitments.

- Experience the societal pressures associated with being the “breadwinner” and not showing weakness, consistent with traditional forms of masculinity. Several student fathers noted the lack of role models — other student fathers who demonstrate positive, healthy behaviors.

- Report poor mental health, including suicidal ideation, during parts of their postsecondary experiences. One study identified that academic stress was significantly and negatively affecting the attention they paid to their children.

- Are disappointed with the lack of support structures specific to student fathers provided by the postsecondary institutions they attend.

- Combat negative stereotypes about being young fathers pursuing their degree.

Health and Basic Needs

According to a study by Ascend at the Aspen Institute, in partnership with JED Foundation, more than two in five student parents experience extreme stress that affects their mental health and educational success.[22] The report provided insight into the mental health experiences of student fathers and mothers. Key takeaways include:

- Over 1 in 5 student fathers considered committing suicide in the 30 days prior, a higher share than among student parents overall (18 percent).

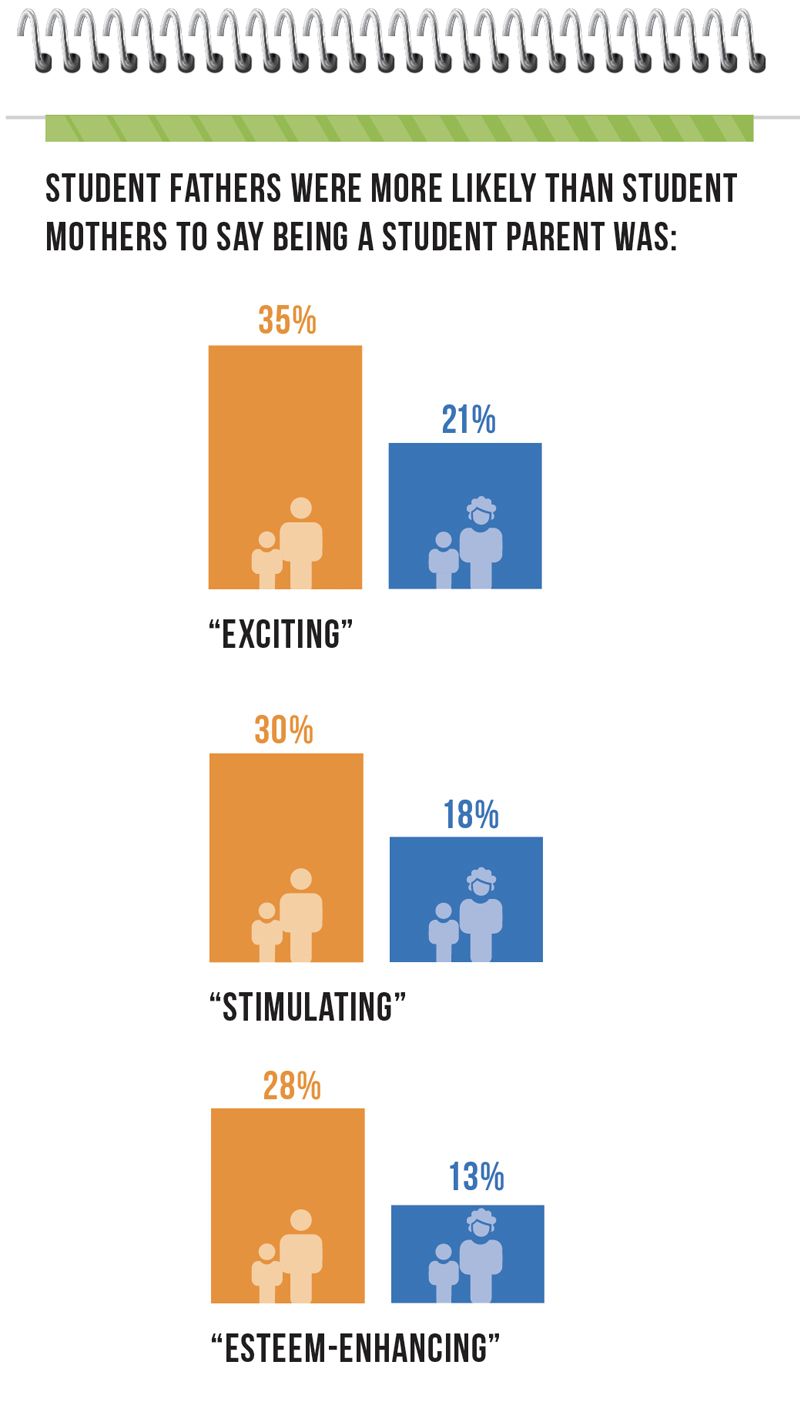

- Student fathers were more likely than student mothers to say being a student parent was “exciting” (35 percent of student fathers compared to 21 percent of mothers), “stimulating” (30 percent vs. 18 percent), and esteem-enhancing (28 percent vs. 13 percent).

- Student fathers were less likely to experience stress (43 percent vs. 50 percent) and anxiety (16 percent vs. 24 percent) than student mothers.

- Eighty percent of the student fathers, compared with 70 percent of student mothers, had help with child care, and among the student parents who had help, fathers were more likely than mothers to receive help from their child’s other parent.

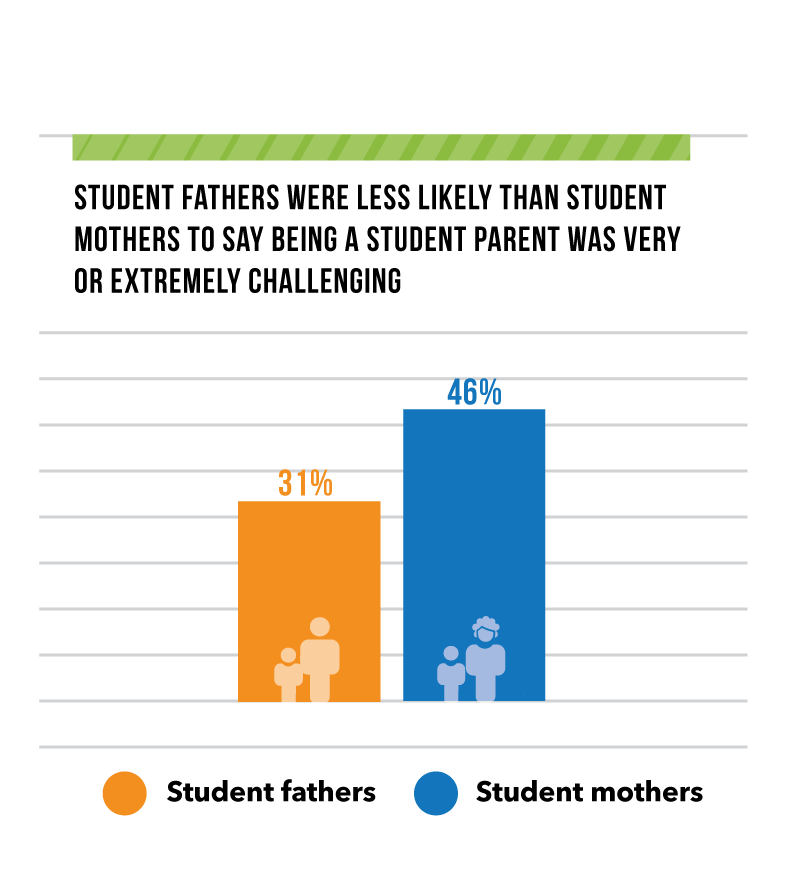

- Student fathers were less likely than student mothers to say being a student parent was very or extremely challenging, and they were less likely to experience guilt often or all of the time (46 percent vs. 31 percent).

In early 2022, the Hope Center released a report[23] on student parents that highlighted racial disparities in basic needs insecurity during the pandemic, including:

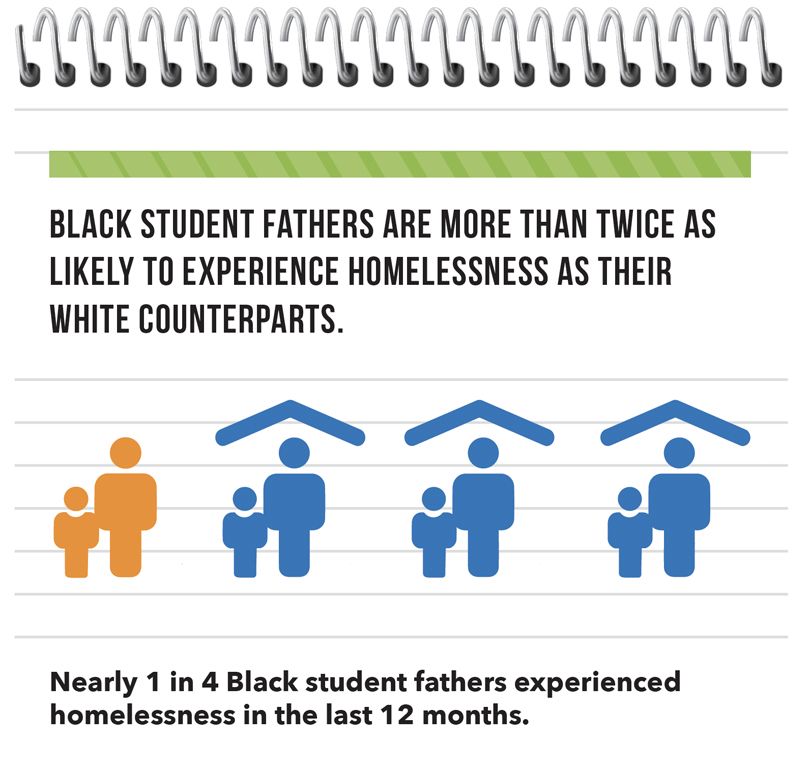

- Two in five Black student fathers experienced income reductions during the pandemic.

- Black student fathers are more than twice as likely to experience homelessness as their white counterparts. Nearly 1 in 4 Black student fathers experienced homelessness in the last 12 months.

- Single Black student fathers were half as likely as single Black mothers to use campus supports (34 percent vs. 69 percent).

This research indicates that focused support would increase the success of student fathers, particularly Black student fathers who experience the highest stop-out rates.[24][25]

“I couldn’t understand when I became student body president at my college why so many men would come and ask me questions about how I was doing it being married, going to school, and working...This information made me understand what they were asking.”

– Drayton Jackson,

2020-2021 Ascend PSP Parent Advisor

Men's College Enrollment

and Adult Learners

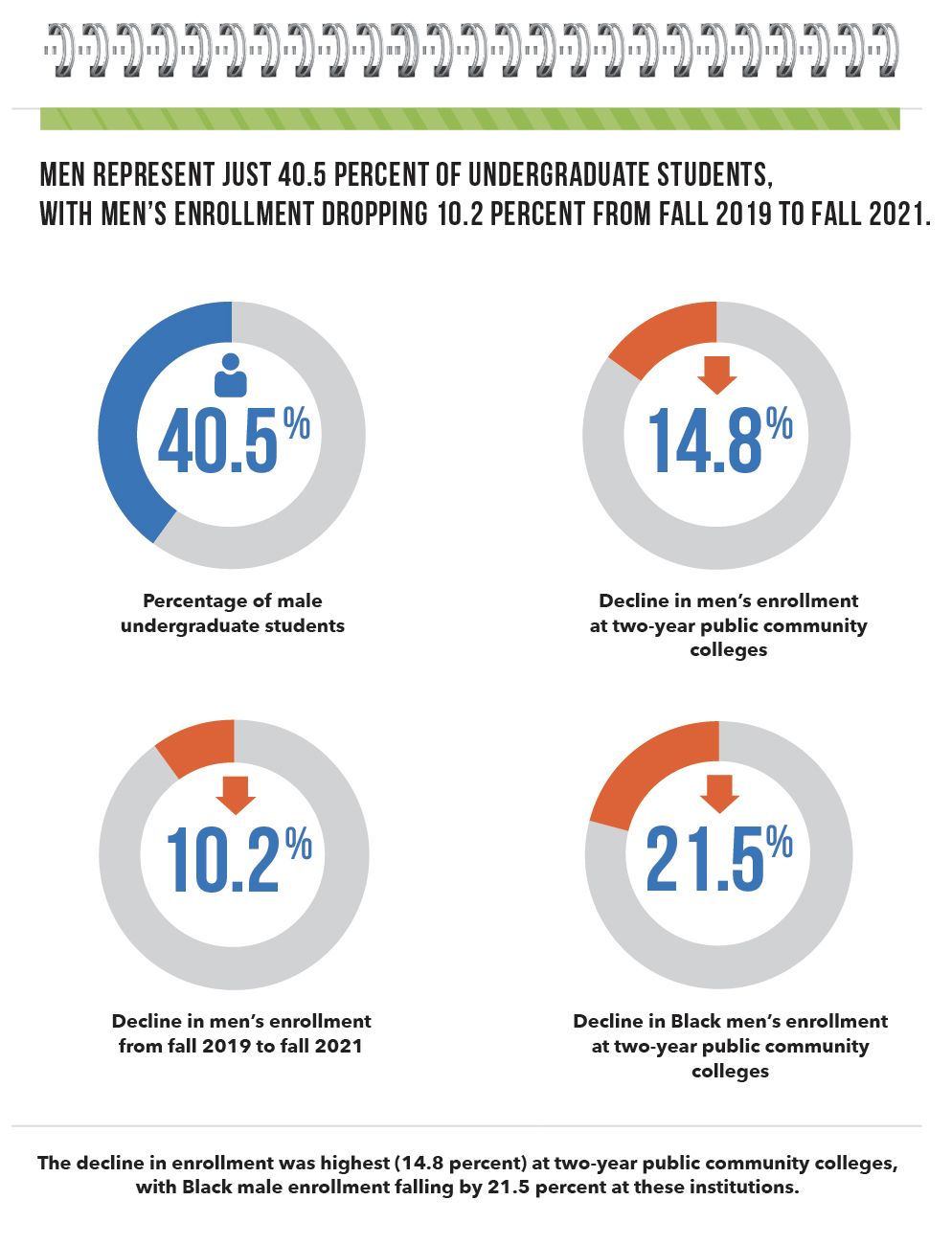

Data on men's college enrollment and male adult learners can fill some of the gap in our knowledge on student fathers. The Male Enrollment Crisis,[26] from the Chronicle of Higher Education, found that men represent just 40.5 percent of undergraduate students, with men’s enrollment dropping 10.2 percent from fall 2019 to fall 2021. The decline in enrollment was highest (14.8 percent) at two-year public community colleges, with Black male enrollment falling by 21.5 percent at these institutions.[27]

Researchers noted that men may be more likely to skip college in pursuit of a decent-paying job, but this decision can negatively impact their long-term earning power. Among adults who do not have a college degree, men were more likely than women to say they “didn’t need more education for the job/career they wanted” or they “just didn’t want” the degree.[28] Although it is true that women need higher levels of education to earn as much as men, a college degree still pays off for men through higher earnings over their lifetimes.[29]

As researchers consider why men’s college enrollment has declined, fatherhood should be explored as a key piece of the puzzle. Raheem Brooks, the program director for the CUNY Fatherhood Academy at LaGuardia Community College, shared that almost all of his students are motivated by a desire to financially provide for their children. The program supports fathers in passing the General Educational Development test (GED), but even though participating fathers use the program to get a better job, only 9 percent of graduates go on to attend college.[30] According to Brooks, many of the fathers in his program say they feel guilty about taking the time to earn a college degree rather than immediately earning money to support their families. Pressures around “breadwinning” instead of pursuing education are often amplified by the fathers’ family members, co-parents, and other influential figures in their lives. Yet, this trade-off comes at a significant cost: men with a college degree earn $30,000 more per year on average than men with a high school degree.[31]

Lumina Foundation’s report exploring the experiences of adult learners who had stopped out, reenrolled, and persisted through or close to graduation[32] highlighted similar issues facing adult learners. More research on the role of fatherhood in the male adult learner experience would help illuminate the broader postsecondary landscape for student fathers.

“When I started my higher education journey, I was a young, single father caring for my infant daughter. It was challenging to find the resources I needed as I juggled my work, school, and parenting, all while struggling with food and housing insecurities.

Although I apply my own personal experiences to help guide my decisions today as the chief executive at a California community college, not all decision-makers have life experiences that give them understanding about unique groups of students. This report will assist policymakers and higher education leaders utilize data to create support programs for a particular group of students that often goes unnoticed.”

– Dr. Mike Muñoz, Superintendent-President,

Long Beach Community College District

Call for Further Research

The lack of attention to student fathers in higher education research is contributing to an educational climate that makes the more than 1 million student fathers in the US nearly invisible. The dearth of research and data on who student fathers are and why they enroll perpetuates a false perception — among both institutional leaders and prospective student fathers themselves — that college is not a place for fathers, limiting fathers’ enrollment and justifying colleges’ lack of support for student fathers. The impact echoes across generations, affecting families’ economic security and children’s well-being.

Additional research is needed to assist practitioners, administrators, and policymakers in cultivating a more inclusive and welcoming college community that supports the success of student fathers. Specifically, researchers should consider exploring:

- More disaggregated data on student parents across different dimensions of social identity. For example, while this chartbook identified that most student fathers are white married men, Black single men who are fathers experience distinct systemic challenges that need more focused exploration.

- More research on student fathers of color in general. Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native/Indigenous, and bi/multiracial fathers are virtually absent from the literature.

- Reasons why fathers without college degrees are not enrolling in college at all or are stopping out of college at concerningly high rates.

- Best practices for the recruitment and retention of student fathers, building on the work of postsecondary institutions that are meeting the needs of student fathers.

Student Parents

- Share your stories about the challenges, joys, and triumphs of your postsecondary journey on social media using #1MillionStudentFathers and the graphics from this chartbook.

- Advocate for student parents by sharing this chartbook with your institution and networks.

Researchers, Practitioners, and Policymakers

- There is an urgent need to better understand through further research the experiences of student fathers and challenges to their attainment of postsecondary degrees. We encourage use of this chartbook as a foundation for additional research.

Everyone

- Start a conversation about what needs to change and the further research and data needed on student fathers.

- Share this research on social media using #1MillionStudentFathers and the graphics from this chartbook.

Drayton Jackson with his sons (Photo Credit: Chona Kasinger)

Drayton Jackson with his sons (Photo Credit: Chona Kasinger)

2020-2021 Ascend PSP Parent Advisor Jesus Benitez with his son (Photo Credit: Desiree Rios)

2020-2021 Ascend PSP Parent Advisor Jesus Benitez with his son (Photo Credit: Desiree Rios)

Ariel Ventura-Lazo with his children (Photo Credit: Sammy Mayo Jr.)

Ariel Ventura-Lazo with his children (Photo Credit: Sammy Mayo Jr.)

This chartbook was prepared by Alex Boesch for Ascend at the Aspen Institute. Ascend is also grateful to Lindsay Reichlin-Cruse, Raheem Brooks, and Jennifer Clark, who provided helpful information and comments in the development of the chartbook. Ascend is deeply appreciative of Drayton Jackson, Dr. Mike Muñoz (Superintendent-President, Long Beach Community College District), Christian Ortiz, Stephan Palmer, and Ariel Ventura-Lazo, student fathers, for sharing feedback and their perspectives for this publication.