Father Figures

Research shows that new dads need mental health supports too. Dr. Craig Garfield explains how we can do better.

Iremember the raindrops falling on the dumpster outside our window. I remember my wife Brittany’s pink polka dot gown, a stylish upgrade over the standard issue hospital garb. I remember the popsicles Brittany excitedly packed that turn into a slushy puddle before she could enjoy them. I remember the white board in our room tallying guesses from nurses and doctors as to whether we were going to have a boy or girl. I remember how practically everyone except Brittany picked girl. (Our baby is, of course, a boy.)

I remember the suddenness with which the contractions intensified. I remember feeling in awe of Brittany’s strength. I remember seeing our son, and telling Brittany, “It’s a boy!” I remember bringing him to Brittany’s chest, and holding him to mine. I remember the team of doctors checking on Brittany around the clock; her pregnancy was high risk. I remember moving to the recovery room, and wondering what we were supposed to do now.

It was one year ago, and every moment from my son’s birth is calcified in my memory. But what I don’t remember is the doctors checking in with me, to see how I was doing. I asked Brittany, and she doesn’t remember either. The entire focus of the medical team was on mother and baby, and to me, that was how it was supposed to be. Dads and all nonbirth partners are supporting actors at best. We are there to make the birthing person comfortable, to bond with the baby, to encourage, I thought. But also to not get in the way.

We were as prepared as a couple could be heading into the birth of our first child, yet I still didn’t consider my own mental health at any point during the birthing process or even in the months after. It felt selfish to do so, like any time spent considering how I was feeling as a new father was time that should have been spent on mom and baby.

That’s why Dr. Craig Garfield’s research resonated so deeply with me. Craig, a 2021 Ascend Fellow, is a professor of Pediatrics and Medical Social Sciences at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and a pediatrician at the Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. His research has shown that the mental health of fathers is an important, and often overlooked, part of perinatal care.

As Craig and his co-author Dr. Tova Walsh explain in their new Health Affairs article, nearly 10 percent of new fathers experience depression. For those whose partners experience postpartum depression, that likelihood increases up to 50 percent. But there are ways to help.

I spoke with Craig about some of those ways, as well as how he became interested in paternal mental health, why it’s important, and the policy changes needed to realize change.

Conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

AF: You've been researching this area for nearly two decades, but it seems like it's taken a while for the field to start to take perinatal mental health seriously when it comes to dads. Why did you see the value in studying this early on?

CG: When I finished residency [in Boston], my son was 18 months old. I had counseled a lot of families, but I really didn't know what I was talking about until I had a kid. And then I realized so much of what we talk about in the clinic finally made sense. After residency, I spent a year at home with my son as a stay at home dad, and that was really what opened my eyes to this whole field. As a white, male physician, I had an incredible amount of social capital. Yet I still was kicked to the curb on the playground, in the mom and tot classes that I was the only male and the only dad in. I realized that, in general, when we think about families, what we're really talking about in the programs that we create, and the supports that we have, from policy to funding, we're really talking about mothers.

After this transformative year with my son, I then went on to get training as a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical scholar and at the University of Chicago, and got a master's in public policy where I learned how – from an economic perspective – people do something when there are incentives for them to do it. And that's really what led me into thinking about fathers and the role fathers play in pediatrics.

We of all fields, concentrating on the child, should be as welcoming as possible of anyone who's taking care of that baby, no matter what their gender, no matter what the relationship is. If they're going to be involved in the health and well-being of that child, we should be welcoming them. And by and large, we really have not been.

2021 Ascend Fellow Craig Garfield

2021 Ascend Fellow Craig Garfield

Craig together with his cohort of Ascend Fellows

Craig together with his cohort of Ascend Fellows

Paternal Mental Health, By the Numbers

What messaging have you seen break through to people who hadn’t considered the mental health of fathers?

There are so many stereotypes that go with fathers and fathering that I think people are constantly trying to fight against. There's the idea that dads aren't involved. Dads don't know what they're doing. They're kind of bumbling fools. If you look at them on TV or in movies, they're always kind of putting the diaper on backwards.

In my experience, having at this point really taken care of and met thousands of dads who are taking care of their baby, they really want to be involved. They may not be sure how to be involved, or even kind of where to start. And I think that's where we really try and make a difference with funding from Ascend at the Aspen Institute to produce the Discharge for Dads videos to start to test this intervention in the newborn nursery. With the Discharge for Dads intervention we are trying to say, Hey, you know what Dad, I get that you are trying to keep it together before the baby's born. and let us give you a little bit of help… here are a handful of videos that we think are some of the most important things for you to learn right now, now that your baby's here, so that you can be the best parent that you can possibly be. And then we offer them short, well-produced, entertaining videos on key things like safe sleep, car seat safety, breastfeeding success, and other topics.

One of the things that I think we have to fight against is this idea that moms know what they're doing. I just have met too many moms that are equally unsure what they're doing, but they're going to figure it out. The dads who I work with may need a little bit more of a push or a nudge to get in there. And I tell all the dads, the more you do that and the earlier you do it, the more confident you will be. And that will pay off down the road.

So many dads are nervous about mom or grandma looking over their shoulder and saying, ‘Oh, you're doing that wrong, you're doing this wrong.’ I say that there really are very few wrongs when it comes to taking care of a baby. Just give it a try. You may not do it exactly the same as your partner does it. You may not do it how your mother did it, but you'll do it how you do it. And that is good enough for your baby.

I’m going to have to share this advice with my wife, Craig. I feel like you’re giving me a pep talk.

That's a real thing, Adam. And it goes back to policy, right? We don't have good policies that support families early after the birth of their child. We're one of the few countries in the world that doesn't have some sort of consistent paid leave for families and for dads in particular. So what happens is, dad is all excited. Dad is trying to figure out how to help and contribute to the family. Dad is working hard, trying to be a good dad at home and realizing that, One way I can help is by making money for the family.

What that discounts then is actually dad having hands on time to understand his baby and learn what makes his baby tick. What is my baby doing when they're crying? Are they wet? Hungry? Tired? All those things come only with time spent with the child without having someone else to be like, Here, you take the baby. Moms will be protective of the dad, thinking I don't want to wake him because he needs to do what he needs to do to keep his job. So that’s a very real thing.

That goes back to the family policies that we have that need to be more supportive of both parents after the birth of a child to get used to that baby, because we know that it pays off down the road.

There's a line in the article that talks about how fathers are less likely to report sadness, and more likely to mask their symptoms to avoid them through numbing behaviors. What role do you see masculinity playing in how we address paternal mental health?

Every dad I've ever met has said, I'm going to break this baby. I’m terrified. But when they're in the nursery, they very much want to be engaged. So it's learning how to hold the baby, how to talk to a baby, recognizing that babies will recognize their dad's voice from hearing his voice while they're inside the mom. If I'm talking to your baby and you're talking to your baby, your baby will turn preferentially to your voice because it recognizes your voice, and telling dads that from the very beginning, this baby recognizes and knows you is so empowering for dads..

The most useful thing for dad to do is to be engaged and involved with their baby. That can be playing on the ground, and dads do a great job of playing with children, even more than mothers. That's one of the things that Michael Yogman has been advocating out in Boston is a prescription for play for dads, because dads will play in a different way with their baby than the way moms do. Dads will use different language than moms do. And all of those things are really beneficial for the health and development of the baby.

The Health Affairs article mentioned several places and entities that are taking some positive steps for dads. Where is support for dads going well?

There's a bit of a sea change happening right now, that's my sense, from when I started in this area two decades ago. There's a real recognition that we need to do more for the partner than we are doing. And that takes shape in a couple of different ways.

For example, with home visiting, they've had a very successful program called Mothers and Babies that helps mothers with their mental health around the perinatal period and around the postpartum period for the baby. At Northwestern, Dr. Darius Tandon and I designed Fathers and Babies, which is an intervention to help fathers' mental health. We designed it in a way that not only does it support fathers to support mothers, but it also supports fathers for their own mental health and well being. And that's part of the shift. It's a shift from saying, let's support fathers so they can support mothers and babies to let's support fathers so they can be the best fathers that they can be. And the downstream effect is that then they actually do help the mothers and the infants to have their best outcomes as well.

It's a shift from saying, let's support fathers so they can support mothers and babies to let's support fathers so they can be the best fathers that they can be.

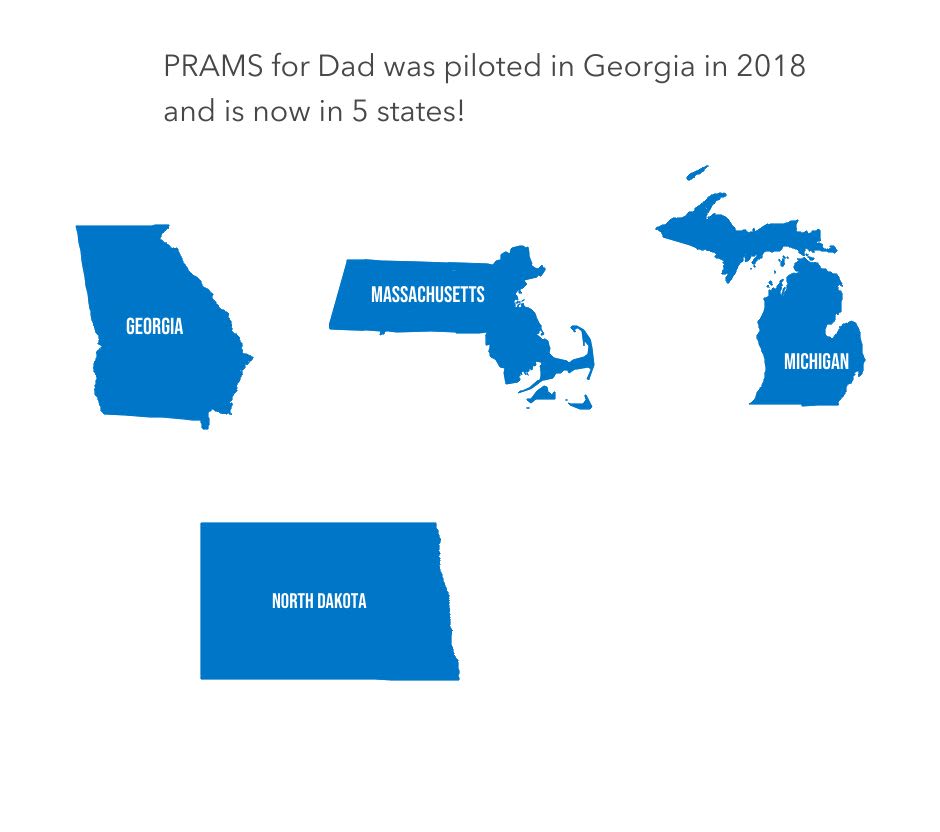

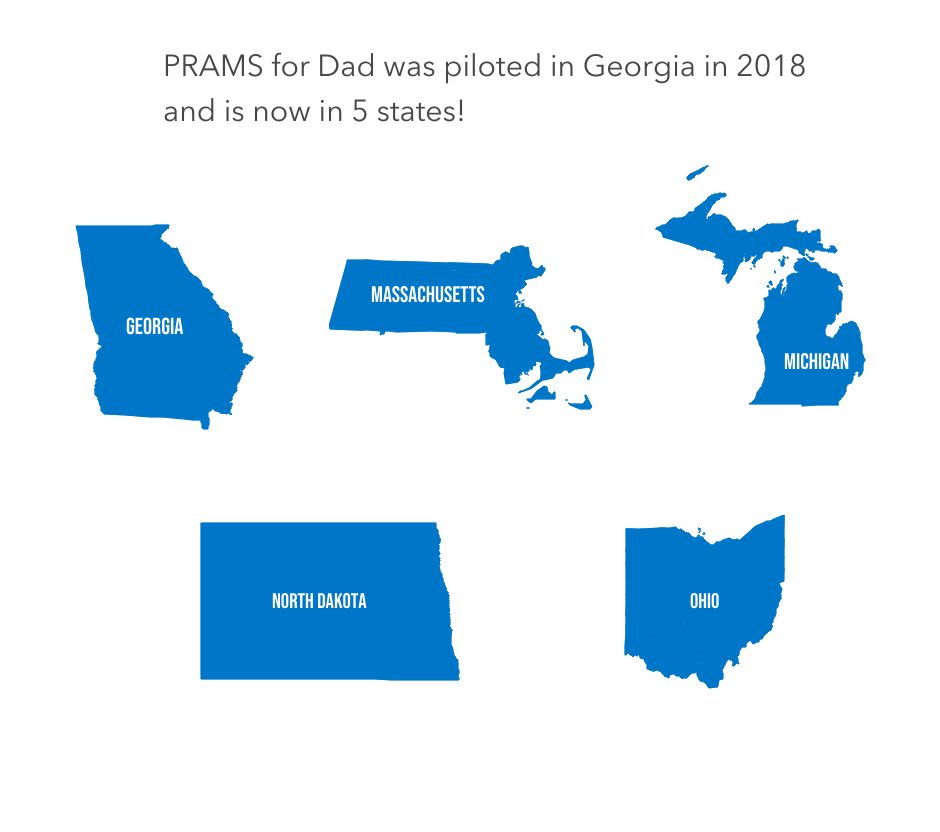

The other example I'll bring up is the PRAMS for Dads projects that we've been doing now for about eight years. PRAMS for Dads is the first public health surveillance program for fathers in the country. We don't have anything like this, we have no way to figure out and put our fingers on the pulse of the health of fathers, right when they are becoming fathers while they're transitioning to fatherhood. We started in Georgia, with pilot funding from the Centers for Disease Control, and we have now expanded to five other states. Our slogan now is “30 by 30" – we hope to get 30 PRAMS for Dads states by 2030. And we are really starting to increase nicely.

The reason why goes back to this sea change where people recognize that if you're just focusing on a mom and a baby, you're missing a key partner. That could be a dad, it could be a female parenting partner, whoever that non birth partner is, we have no line of sight into how they're doing. And if we can improve that, we can actually, I think, make better outcomes for children, mothers, and families collectively.

How do you see the sea changing moving forward? Are there new frontiers of research that you're particularly excited about? Or is it more that the research is established now we need to really get the word out?

One is that more and more men want to be involved with their children. And I think the pandemic showed us where there's a real uptick in father's involvement with their children during the pandemic. And now, I think there's an expectation that work is going to allow me some ability to be with my child, that's one part of the sea change,

My other hope in the sea change is that we have different ways of funding the work for fathers, because we have a lot of really good work going on and scaling it to the level we need understanding and improving the health of families in the country is going to take resources. Right now, there's a sense, I think that the pie is finite, that any money we take to study fathers or support fathers or provide programming for fathers is taking money away from mothers. That it’s a zero sum game. That doesn't make any sense.

When you think about the child, I think you want what's best for both parents, regardless of marital status, and whatever type of parent they are. And that's what we should be building, supporting and trying to understand in our families today.